|

En regardant en détail ce qui s'ordonne dans les images de Pietro Ruffo, nous avons la nette impression que les choses se passent dans divers espaces, qu'il y a une simultanéité entre l'espace (d'un territoire à un autre) et le temps où s'effectuent les gestes de l'artiste, ses interventions sur les "cartes", comme si nous étions dans une autre pièce de la réalité et du monde. L'imaginaire de Pietro Ruffo a pour fonction de nous donner à voir autre chose, à travers ses dessins, ses coléoptères découpés en deux dimensions et ses "infiltrations", que la seule représentation d'une réalité tout au moins saisissable par tous. Il nous entraîne vers un autre monde aux repères transformés et nous inspire des interrogations.

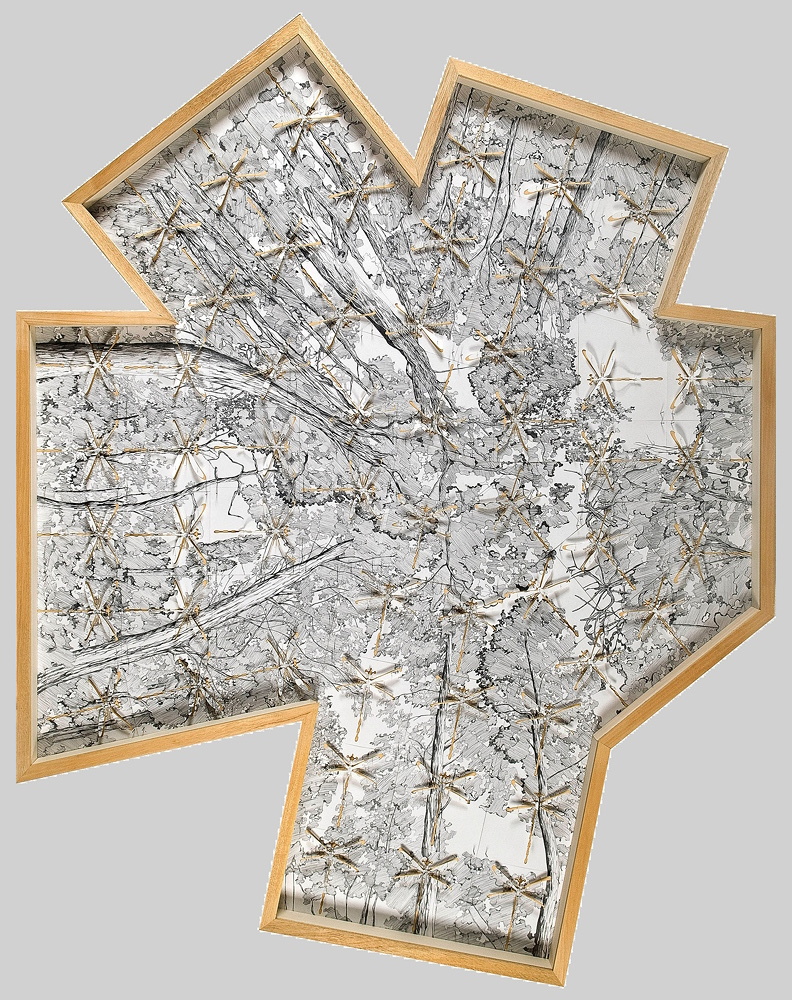

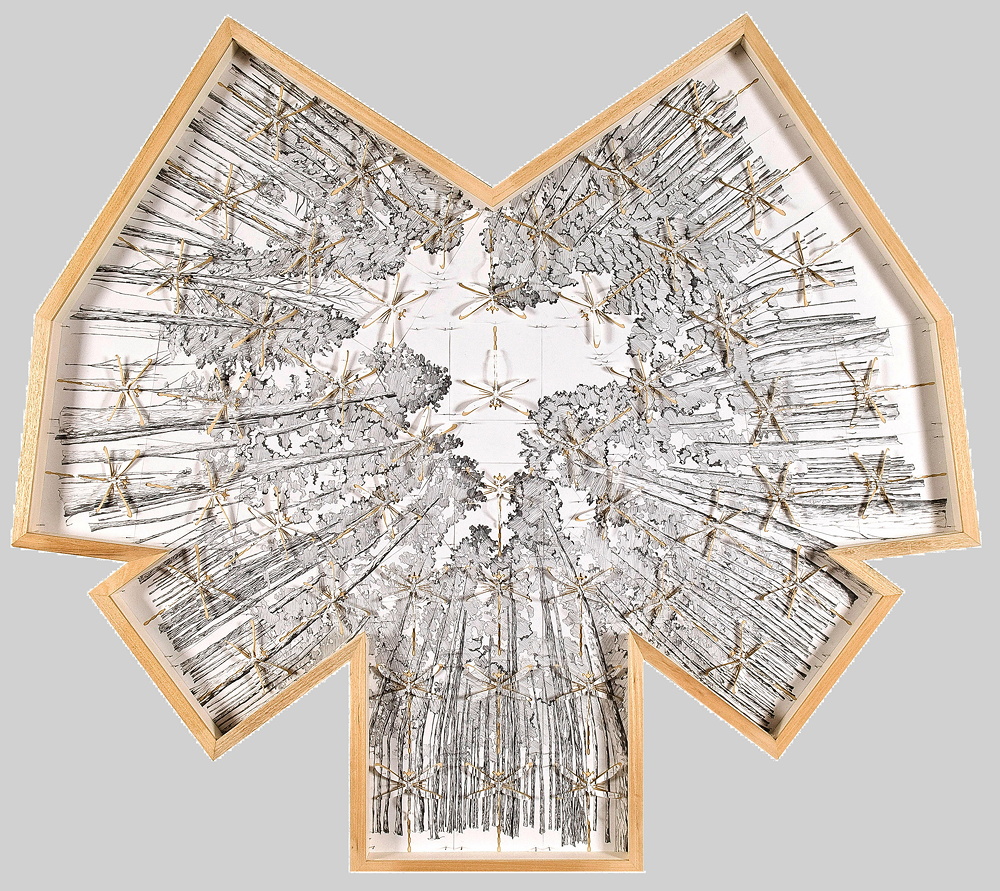

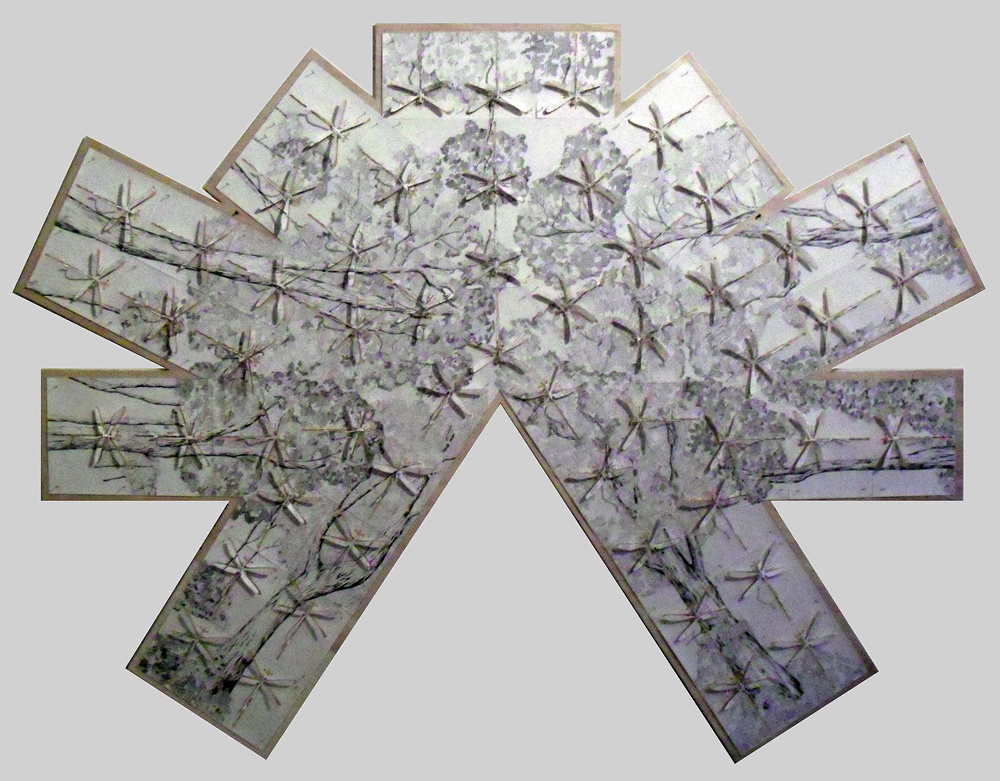

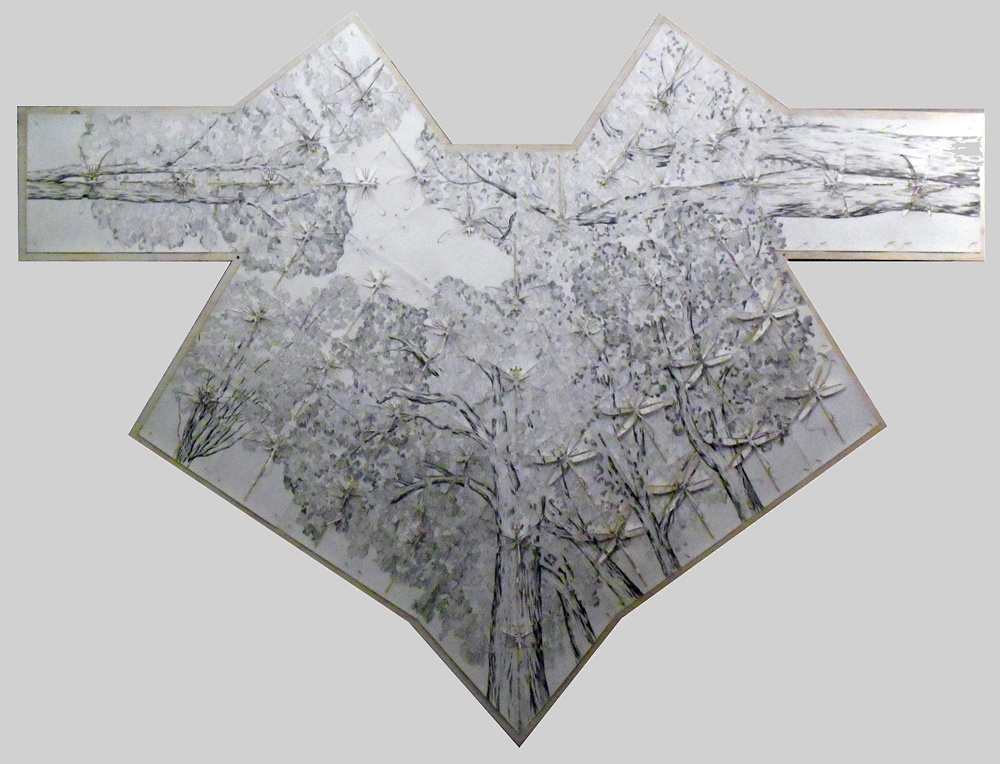

L'esthétique de Pietro Ruffo s'appuie sur plusieurs paramètres. Ses images de paysages insolites aux arborescences éclatées sont dessinées au graphite et à l'encre de chine. Il s'approprie les cartes géographiques et les transforme par des signes dont les particularités apparaissent ou sautent à l'œil du spectateur. Ces cartes ont été contaminées, les territoires ont subi ce que l'on pourrait appeler les "nouvelles plaies d'Egypte" - en référence, bien sûr, à la Bible. Sa recherche s'appuie sur les mouvements géopolitiques, des aspects non seulement de la politique internationale, mais aussi des idéologies et des religions. Lorsque nous regardons en le détail les œuvres imaginées et conçues par Pietro Ruffo, elles nous interpellent au-delà de l'attrait qu'elles peuvent exercer sur le spectateur par leur charge émotionnelle. Ces scarabées, ces libellules ont quelque chose d'insolite. Les sinuosités des tableaux, les dessins, la couleur, inventent un espace scénique inédit dans la circulation humaine. Pietro Ruffo dit que ses oeuvres : "trouvent leur ancrage dans l'espace sociologique et dans l'Histoire dans laquelle nous vivons." On peut suggérer ici qu'il y a une entité relationnelle entre le public et l'œuvre d'art. L'artiste établit, entre son œuvre et le regard qu'on porte sur elle, un ensemble de métaphores qui explicite ses points de vue, tout en privilégiant une vision poétique. Les coléoptères qui figurent dans son œuvre sont autant d'allégories des comportements humains. De même que La Fontaine inventa des modèles et un langage en représentant les caractères humains par des animaux. "La relation humaine qui s'établit avec les libellules, par exemple, évoque la contamination des territoires les uns par les autres : l'Afrique par la Chine ou l'Amérique latine par l'Amérique du Nord, etc." Ainsi, Ruffo superpose la carte de la Chine sur l'Afrique pour mettre en exergue les conflits latents, les instrumentalisations politiques qui s'exercent au-delà des continents. Les insectes sont des armées qui dorment. "Les cerfs-volants (variété de scarabée) font éclore leurs œufs dans les plantes ; ils dévorent les feuilles pour prendre vie, pour se régénérer, ce sont en fait des formes parasitaires. Ils mangent le support à partir duquel ils s'envoleront."

Pietro Ruffo a consacré dans une autre séquence de son travail une réflexion sur des thèmes philosophiques, et sur des théories d'économie politique, en utilisant dans ses images infusées d'informations quelques textes des traités politiques entre les nations. Ces textes apparaissent en filigrane dans ses œuvres. Dans telle œuvre, les traités sont rongés par les insectes. Mais n'est-ce pas Hugo qui disait que : " L'homme est un rongeur." ! Ici et là, ce sont de nombreuses cartes du Moyen-Orient : Syrie, Irak, Liban, Palestine, Israël et de l'Iran, qui relatent les formes stratégiques de son discours. L'artiste détourne les drapeaux des pays, change leurs emblèmes et leurs couleurs, pour les transposer en d'autres contrées.

Pietro Ruffo contamine par sa poétique la réalité ordonnée. Ainsi il élabore de nouveaux territoires, subtilement modifiés, qui expriment son esthétique. Il formule de nouvelles hypothèses qui interagissent sur le regard du spectateur. Pourquoi les scarabées ou les libellules, ces demoiselles si fines et jolies, à l'instinct carnassier, semblent-ils sortir de la carte dessinée en relief ? Les divers éléments se fondent avec des crânes et des mâchoires non identifiées, sur le papier dessiné parfois au bic. Tel ce Beetle flag, drapeau composé de scarabées sur des textes de prières hébraïques, ou comme ce char de bois et de papier où figurent les mêmes insectes sculptés, Youth of the hill. Tel encore ce drapeau du Commonwealth, Union Jack, où sont reproduits des traités politiques. Les références aux œuvres d'Alighiero Boetti, de Pino Pascali et ses "canons" ou aux Flags de Jasper Johns sont implicites chez Ruffo. Ses proliférations révèlent une idée récurrente : le "parasitage" qui s'opère constamment.

Pour la série de portraits de philosophes, I sei traditori della libertà, les "Six traîtres de la liberté", les libellules semblent perforer le papier, en surimpression. Qui sont-ils ces six traîtres de la liberté ? "En 1952, lors d'une émission à la BBC, Isaiah Berlin, le philosophe anglais, donne six conférences sur ce thème, en évoquant Helvétius, Rousseau, Hegel, Fichte, Joseph de Maistre, Saint-Simon (le rival de Charles Fourier, l'utopiste anglophile, qui avait élaboré son système productiviste pour réduire les maux de la collectivité, il s'est finalement trompé, car nous vivons dans ce modèle historique… Une vision en rien utopiste ! (c'est moi qui souligne), philosophes matérialistes et idéalistes." Selon Isaiah Berlin, chacun d'eux ont forgé une conception de la liberté collective pour les individus. "Les régimes totalitaristes s'en sont inspirés en partie. J'ai voulu montrer à travers ces six portraits, comment les libellules pouvaient déstructurer leur image. Ces coléoptères se déplacent et bougent constamment, à l'horizontale, comme chacun peut l'observer. Je tenais à introduire l'idée de fragilité à travers la conception de mes images. Cette fragilité – par métaphore – instaure une relation avec le concept de liberté." Le philosophe anglais a publié ses Deux concepts de liberté, en 1958. Il y développe ses idées sur la liberté positive et la liberté négative, auxquelles Ruffo se réfère, en dessinant ces territoires "grignotés" par les nouvelles puissances mondiales. Le monde glisse jour et nuit en silence, comme l'écrit Pline l'Ancien. "La liberté individuelle doit se libérer de l'état. J'appartiens à une société qui est arrivée à une forme de liberté plus grande, dans la mesure où l'on peut donner quelque chose à la collectivité, à l'autre. Isaiah Berlin considérait, de ce point de vue, que le système soviétique (durant la guerre froide) devait être à l'avant-garde. Mais il n'en a rien été ! Le modèle russe s'est avéré être une contrainte plus qu'autre chose." En vue d'une nouvelle exposition, Ruffo a interviewé six philosophes italiens sur les échecs de ces six traîtres… Il s'agit d'Aldobrandini, Maffettone, Marramao, Santambrogio, Lecaldano et Carter qui ont apporté leur propre réflexion sur le monde libéral.

Le sujet de la liberté est un sujet "géographique", culturel et spirituel, ajoute-t-il : une des raisons pour lesquelles, artistes et philosophes participent à sa réflexion artistique. Lors de l'exposition à Paris, on verra le rapport entretenu entre les territoires et l'empreinte sur les drapeaux : la Chine sur l'Afrique, la Chine sur l'Amérique Latine, la Chine sur la Russie. "Toutes ces œuvres sont pour moi une expression d'une autre vision de la liberté plus individuelle. Les drapeaux dessinés avec des crânes sur des cartes géographiques sont une manière de réintroduire une réflexion sur les vanités et l'espèce humaine." Une de ses visions m'évoque Stanley Kubrick quand il dit : "L'homme du XXe siècle a été lâché sur une mer non cartographiée. S'il veut rester sain pendant son voyage, il lui faut quelqu'un à aimer, quelqu'un qui soit plus important à ses yeux que lui-même."

Le monde des images est extrême. Il faut retrouver cette faculté de regarder, car elle réunit toutes les sciences, à partir de laquelle celles-ci doivent se développer, comme le suggère Peter Handke. Avec les documents et les ruines se forme l'histoire telle que l'entend l'Europe. La structure capillaire et macroscopique des espaces et des territoires doit se planifier comme le révèlent les images de Ruffo. Ainsi l'œil existe à l'état sauvage. Le naturaliste Buffon a observé le monde libre des animaux – des merveilles de précision – et des insectes en poète et en styliste, non comme l'entomologiste Jean-Henri Fabre, plus tard. La nature invente toujours des situations indéchiffrables et des phénomènes prodigieux. Quand on nomme les animaux, ils prennent les formes multiples de l'allégorie et du symbole. Ils réactivent notre imaginaire en se portant sur les événements du monde pour les investir d'une dimension poétique. L'alphabet et le geste de Pietro Ruffo recèlent des combinaisons inédites, qu'il ravive en leur donnant une tridimensionnalité. Tenons-nous alors devant un tableau comme devant un personnage, disait Schopenhauer. Attendez qu'il vous parle. L'œil écoute !

|

Guardando in dettaglio il modo in cui si organizzano le immagini di Pietro Ruffo, abbiamo la nitida impressione che le cose accadano in vari spazi. Che ci sia una simultaneità tra lo spazio (da un territorio all'altro) e il tempo nel quale si eseguono i gesti dell'artista, i suoi interventi sulle "cartine", come se ci trovassimo in un'altra stanza della realtà e del mondo. L'immaginario di Pietro Ruffo ha la vocazione di farci vedere un qualcosa di diverso, attraverso i suoi disegni, i suoi coleotteri ritagliati in due dimensioni e le sue "infiltrazioni", rispetto all'unica rappresentazione di una realtà più o meno percepibile da tutti. Ci trasporta verso un altro mondo, dai punti di riferimento trasformati, e c'ispira degli interrogativi.

L'estetica di Pietro Ruffo si fonda su vari parametri. Le sue immagini di paesaggi insoliti dalle arborescenze frammentate sono disegnate con grafite e inchiostro di china. Si appropria delle carte geografiche e le trasforma grazie a dei segni, le cui peculiarità appaiono o balzano all'occhio dello spettatore. Queste carte sono state contaminate, i territori hanno subito quelle che potremmo chiamare le "nuove piaghe d'Egitto" – riferendoci, ovviamente, alla Bibbia. La sua ricerca si basa sui movimenti geopolitici, degli aspetti non solo della politica internazionale, ma anche delle ideologie e delle religioni. Osservando in dettaglio le opere immaginate e concepite da Pietro Ruffo, ci accorgiamo che c'interpellano ben più che per la mera attrazione che possono esercitare sullo spettatore grazie alla loro forza emozionale. Questi insetti, scarabei o libellule, hanno qualcosa d'insolito. La sinuosità dei quadri, i disegni, il colore, inventano uno spazio scenico inedito nella circolazione umana. Pietro Ruffo dice che le sue opere "Trovano il loro ancoraggio nello spazio sociologico e nella Storia nella quale viviamo". Possiamo suggerire qui che ci sia un'entità relazionale tra il pubblico e l'opera d'arte. L'artista stabilisce, tra la sua opera e lo sguardo che portiamo su di essa, un complesso di metafore che ci spiega i suoi punti di vista, privilegiando al contempo una certa poesia. I coleotteri scelti per apparire in quest'opera sono le allegorie dei comportamenti umani. Come La Fontaine, che ha rappresentato i caratteri umani per mezzo di animali, inventando dei modelli e un linguaggio. "La relazione umana che si stabilisce con le libellule, per esempio, evoca la contaminazione reciproca dei territori. L'Africa con la Cina, l'America latina con l'America settentrionale, e così via". Ruffo sovrappone così la cartina della Cina su quella dell'Africa, per evidenziare i conflitti latenti e le strumentalizzazioni politiche che si esercitano oltre i continenti. Gli insetti sono degli eserciti che dormono. "I cervi volanti (varietà di scarabei) fanno schiudere le loro uova nelle piante; divorano le foglie per prendere vita, per rigenerarsi; sono, insomma, delle forme parassitarie. Mangiano il supporto dal quale s'involeranno".

In un'altra sequenza del suo lavoro, Pietro Ruffo ha consacrato le sue opere a una riflessione su alcuni temi politici filosofici ?, le teorie d'economia politica, utilizzando nelle sue immagini infuse d'informazioni alcuni stralci testuali dei trattati politici transnazionali. Appaiono tra le righe delle sue opere, con tocchi discreti. In una delle opere, i trattati sono rosicchiati dagli insetti. Ma non era forse proprio Victor Hugo che diceva: "L'uomo è un roditore"? Qua e là, ecco numerose cartine del Medio Oriente – Siria, Iraq, Libano, Palestina, Israele e Iran – che menzionano le forme strategiche del suo discorso. L'artista svia le bandiere dei paesi, modifica i loro emblemi e i loro colori per trasporli su altre nazioni.

Pietro Ruffo contamina con la sua poesia l'ordinata realtà, elaborando così dei nuovi territori, sottilmente modificati, che esprimono la sua estetica. Formula delle nuove ipotesi che interagiscono con lo sguardo dello spettatore. Perché gli scarabei o le libellule, queste damigelle così delicate e graziose, dall'istinto carnivoro, sembrano uscire dalla cornice della cartina disegnata come se fossero dei bassorilievi? I vari elementi si fondono con crani e mascelle non identificate sulla carta disegnata talvolta con una penna a sfera. Come in Beetle flag, bandiera composta di scarabei su testi di preghiere ebraiche. Come in Youth of the hill, carro di legno e carta dove appaiono gli stessi insetti scolpiti. Come nella bandiera del Commonwealth, l'Union Jack, dove sono riprodotti dei trattati politici. I riferimenti alle opere di Alighiero Boetti, di Pino Pascali, con i suoi "cannoni", o a Flags, di Jasper Johns, sono impliciti nell'opera di Ruffo. Ma le sue proliferazioni rivelano un'idea ricorrente: il "parassitaggio" che si opera costantemente.

Nella serie di ritratti di filosofi, I sei traditori della libertà, le libellule sembrano perforare la carta, come in sovrimpressione. Ma chi sono questi sei traditori della libertà? "Nel 1952, nel corso di una trasmissione della BBC, Isaiah Berlin, il filosofo inglese, tenne sei conferenze su questo tema, evocando Helvétius, Rousseau, Hegel, Fichte, Joseph de Maistre e Saint-Simon (il rivale di Charles Fourrier, l'utopista anglofilo che aveva elaborato il proprio sistema produttivistico per ridurre i mali della collettività, alla fine si è sbagliato, visto che viviamo in questo modello storico… Una visione per niente utopica! sottolineo io), filosofi materialisti e idealisti". Secondo Isaiah Berlin, ognuno di loro ha forgiato una concezione della libertà collettiva per gli individui. "I regimi totalitari se ne sono in parte ispirati. Ho voluto mostrare, attraverso questi sei ritratti, come le libellule potessero destrutturare la loro immagine. Questi coleotteri si spostano e si muovono senza sosta, all'orizzontale, come ognuno può vedere. Tenevo inoltre all'introduzione dell'idea di fragilità, attraverso la concezione delle mie immagini. Questa fragilità "per via metaforica" instaura una relazione con il concetto di libertà". Il filosofo inglese ha pubblicato i suoi Due concetti di libertà nel 1958. Vi sviluppa le sue idee sulla libertà positiva e negativa, a cui Ruffo si riferisce, tra l'altro, disegnando questi territori "rosicchiati" dalle nuove potenze mondiali. Il mondo scivola giorno e notte in silenzio, come scrisse Plinio il Vecchio. "La libertà individuale deve liberarsi dello Stato. Appartengo a una società che ha raggiunto una forma di libertà più grande, nella misura in cui si può dare qualcosa alla collettività, all'altro. Isaiah Berlin considerava, da questo punto di vista, che il regime sovietico (durante la guerra fredda) dovesse essere all'avanguardia. Ma così non è stato! Il modello russo si è rivelato essere più un vincolo che altro". Per una nuova mostra, Pietro Ruffo ha intervistato sei filosofi italiani sui fallimenti di questi sei traditori… Si tratta di Aldobrandini, Maffettone, Marramao, Santambrogio, Lecaldano e Carter, che hanno espresso la loro riflessione personale sul mondo liberale.

Il soggetto della libertà è un soggetto "geografico", culturale e spirituale, aggiunge l'artista. Uno dei motivi che spiegano perché artisti e filosofi partecipino alla sua riflessione artistica. Durante la sua mostra parigina, vedremo il rapporto che esiste tra i territori e l'impronta sulle bandiere: la Cina sull'Africa, la Cina sull'America latina, la Cina sulla Russia. "Tutte queste opere sono, per me, un'espressione di un'altra visione della libertà, più individuale. Le bandiere disegnate con dei crani sulle cartine geografiche sono un modo di reintrodurre una riflessione sulle vanità e sulla specie umana". Una delle sue visioni mi fa pensare a Stanley Kubrick quando dice: "L'uomo del XX secolo è stato abbandonato su un mare non cartografato. Se vuole restare sano durante il suo viaggio, ha bisogno di qualcuno da amare, qualcuno che, ai suoi occhi, sia più importante di lui stesso".

Il mondo delle immagini è estremo. È necessario ritrovare questa facoltà di guardare, perché essa riunisce tutte le scienze ed è da lì che le scienze devono svilupparsi, come ce lo suggerisce Peter Handke. La concezione storica dell'Europa si forma con documenti e rovine, al contrario di quanto avviene sugli altri continenti. La struttura capillare e macroscopica degli spazi e dei territori deve essere pianificata, come lo rivelano le immagini di Ruffo. Così, l'occhio esiste allo stato brado. Il naturalista Buffon ha osservato il mondo libero degli animali – delle meraviglie di precisione – e degli insetti come un poeta e uno stilista, non come l'entomologo Jean-Henri Fabre, un secolo dopo. La natura inventa sempre delle situazioni indecifrabili e dei fenomeni prodigiosi. Quando si battezzano gli animali, essi assumono le forme multiple dell'allegoria e del simbolo. Riattivano il nostro immaginario posandosi sugli eventi del mondo, per investirli di una dimensione poetica. L'alfabeto e il gesto di Pietro Ruffo celano delle combinazioni inedite e lui le ravviva, offrendo loro una tridimensionalità. Teniamoci davanti a un quadro come davanti a una persona, diceva Schopenhauer. Aspettate che vi parli. L'occhio ascolta!

traduit du français par GianCarlo Pagliasso

|

Take a close look at how Pietro Ruffo's images are configured and you'll

get the distinct impression that things are happening in different areas of

the work, that there is a kind of simultaneity between the space (from one

territory or region to another) and the time during which the artist's

gestures and map-based interventions are executed as if the spectator had

stepped into another room, far from reality and the world itself. Through

his drawings, two-dimensional beetle cut-outs, and "infiltrations", Pietro

Ruffo's imaginative world conveys a reality that is radically different from

the representation of reality which is generally perceived. He leads us into

another world, filled with newfangled landmarks and reference points, and

calls our own sense of reality into question.

Ruffo's aesthetic is based on several criteria. His images of highly unusual

landscapes with exploding arborescences are done in lead and India ink.

He appropriates and transforms geographical maps using symbols whose

unusual features capture the viewer's eye. The maps have been

"contaminated", the regions having been hit by what could be dubbed

"the new plagues of Egypt"—with all of the obvious biblical allusions. His

artistic research is based on geopolitical movements and trends, drawing

on international politics as well as ideologies and religions. In all their

detail, the works imagined and created by Pietro Ruffo go beyond their

visual appeal, transfixing the viewer with their emotional impact. His

insects, beetles, scarabs and dragonflies are highly unusual. The curves of

the paintings, the drawings, and the colours create a scenic space that is

totally new with respect to human gestures. Pietro Ruffo maintains that

his works "find their anchoring in sociological space and in History which

we inhabit". We can hypothesize that there is a "relational entity" between

the public and the work of art. Through his work and how it is perceived,

the artist establishes an ensemble of metaphors that speak about his

perspectives and positions while highlighting a certain poetic vision ? The

beetles in this work are allegories of human comportment, similar to the

way in which La Fontaine represented human characters using animals,

by inventing models and a language. "The human relationship with

dragonflies, for example, brings to mind the contamination of one region

by the next—Africa by China or Latin America by North America, etc." In

this way, Ruffo superimposes maps of China and Africa to underscore the

latent conflicts and the political instrumentalisation taking the world over.

Insects are slumbering armies. "Stag beetles lay their eggs in plants; they

devour leaves to feed their existence, to regenerate ; they are in fact

parasitic forms. They eat the very base from which they will eventually take flight."

In another sequence from his work, Ruffo focuses on philosophical

themes and polito-economic theories by using texts of political treaties

between nations in his information-laden images. They appear as

watermarks in his works through subtle touches. In such a work, the

treaties are eaten away by insects. But wasn't it Victor Hugo who said

"L'homme est un rongeur" (‘Man is a rodent'). Several maps of the

Middle East—Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel and Iran—can be

found in the work, conveying the strategic forms of his discourse. The

artist does his own personal take on national flags, altering their emblems

and colours and transposing them onto other lands.

Ruffo contaminates the ordered reality through his poetics. He elaborates new territories and

regions, subtly altered, to express his aesthetic. He formulates new

hypotheses that interact with the viewer's gaze. Why do the beetles and

dragonflies—fine and lovely demoiselles with carnivorous instincts—seem

to loom outside the frame of the map drawn as if in relief ? The various

elements merge and converge with the unidentified skulls and jaws on

paper, at times drawn using biro. Like Beetle Flag, a flag made of scarabs

on a backdrop of Hebrew prayer texts. Like the wood and paper military

tank featuring the same sculpted insects in Youth of the Hills. Like the

Commonwealth flag Union Jack, with its reproductions of political treaties.

References to works by Alighiero Boetti, Pino Pascali and his "cannons"

and Jasper Johns's Flags are implicit in Ruffo's works. But a recurring idea

is found throughout his artistic output : ever-constant unending

exploitation.

In his series of portraits of philosophers, I sei traditori della

libertà, or "six traitors of liberty", the dragonflies seem to actually perforate

the paper in the way that they are superimposed. Who exactly are these

six traitors of liberty? "In 1952, as part of a BBC programme, the British

philosopher Isaiah Berlin gave six talks on this theme, evoking Helvetius,

Rousseau, Hegel, Fichte, Joseph de Maistre, and Saint-Simon (the rival of

the Anglophile utopian philosopher Charles Fourier, all materialistic and

idealistic philosophers, who had devised a productivist system to help

diminish the evils of communities—yet he was mistaken in the long run,

for our current world is based on this type of historic model—hardly a

utopia! (my emphasis here)." Isaiah Berlin felt that each had forged a

conception of collective liberty for individuals. "In part, totalitarian regimes

drew on this for inspiration. I wanted to demonstrate through these six

portraits how dragonflies could deconstruct their image. These insects are

constantly moving and flitting about, horizontally, as has been observed. I

wanted to introduce the notion of fragility in doing these images. This

fragility—by metaphor— establishes a relationship with the concept of

liberty."

The British philosopher published his Two Concepts of Liberty in 1958. In it

he developed his ideas about positive and negative liberty, which Ruffo

refers to by depicting these lands that are "eaten away" by the new

superpowers, as well as by others. "The world turns round day and night in

silence", wrote Pliny the Elder. "Individual liberty must free itself from the

State. I belong to a society which has brought about a greater form of

liberty in this that we can give something to the community, to the other.

Isaiah Berlin believed, from this point of view, that the Soviet system

(during the Cold War) was avant-garde. But it wasn't at all! The Russian

model proved to be a constraint more than anything else." For a new

exhibition, Pietro Ruffo interviewed six Italian philosophers about the

failures of these six traitors. Aldobrandini, Maffettone, Marramao,

Santambrogio, Lecaldano and Carter, each of them gave their opinion on liberalism. The subject of liberty is a "geographical", cultural and spiritual subject, Pietro Ruffo adds. This is one of the reasons why artists and philosophers are part of his artistic process. During the Paris exhibition, we will see the relationship between territories and regions and the imprint of the flags : China on Africa, China on Latin America, China on

Russia. "To me, all of these works are an expression of another vision of

liberty that is more individual. Flags drawn with skulls on geographical

maps are a way of making people think once again about vanitas and the

human race." One of his visions brings to mind Stanley Kubrick when he

said: "Man in the 20th century has been cut adrift in a rudderless boat on

an uncharted sea. If he is going to stay sane throughout the voyage, he

must have someone to care about, someone that is more important than

himself."

The world of images is extreme. We need to bring back the ability to look,

watch and observe, for this ability reunites all branches of science, thus

providing the basis for science to flourish, as Peter Handke suggests.

History, as Europe sees it, takes shape by means of documents and ruins,

which is not the case in other continents. The capillary and macroscopic

structure of spaces, lands and territories must be organised, as Ruffo's

images show. In this way, the eye exists in the wild. Buffon, the French

naturalist, observed the animal world—marvelous creatures in their

precision—as well as insects as a poet or designer would, not as

entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre would do a century later. Nature always

invents indecipherable situations and stupendous phenomena. When

animals are named, they take on the multiple forms of allegory and

symbol. They rekindle our imagination by having a bearing on world

events, giving them a poetic dimension. Pietro Ruffo's artistic vocabulary

and gesture feature highly unusual associations and juxtapositions. He

revives them by giving them three-dimensionality. So let's heed

Schopenhauer and stand before a work of art as if it were a prince. Wait

until it speaks to you. The eye is listening!

Parick Amine

Paris, 2011/2020

Translation by Elizabeth Ayre & Jerome Reese

|